Lèse-Majesté Cases are Multiplying

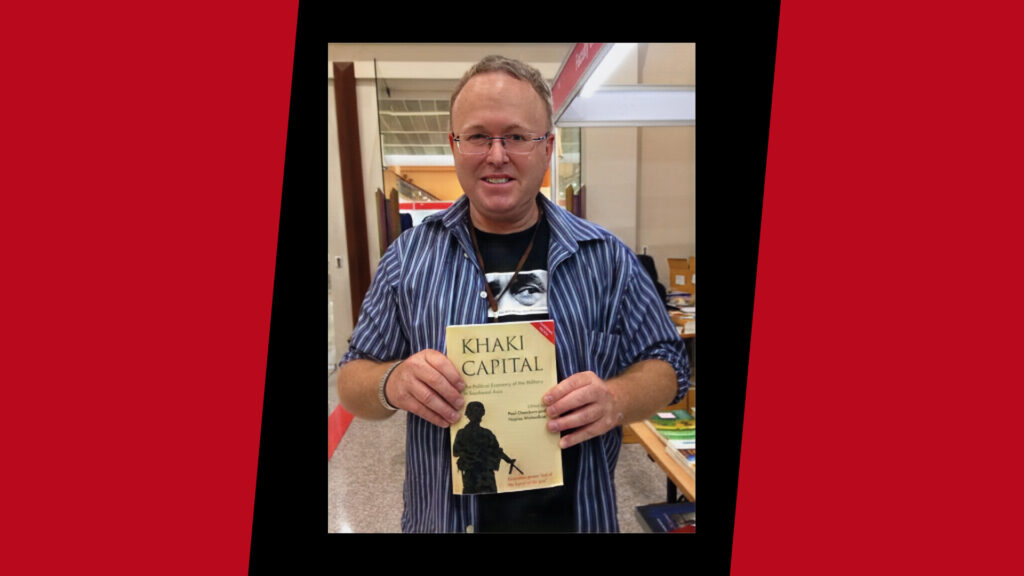

The controversial issue of the lèse-majesté law is not only a hot debated within Thailand, but also in the wider world. There have been two kinds of reaction from the international community to the discursive use of the lèse-majesté law: a critical view from Western governments, international organisations, academic society and foreign media, and; a rather timid position endorsed by Thailand’s neighbours in the region.

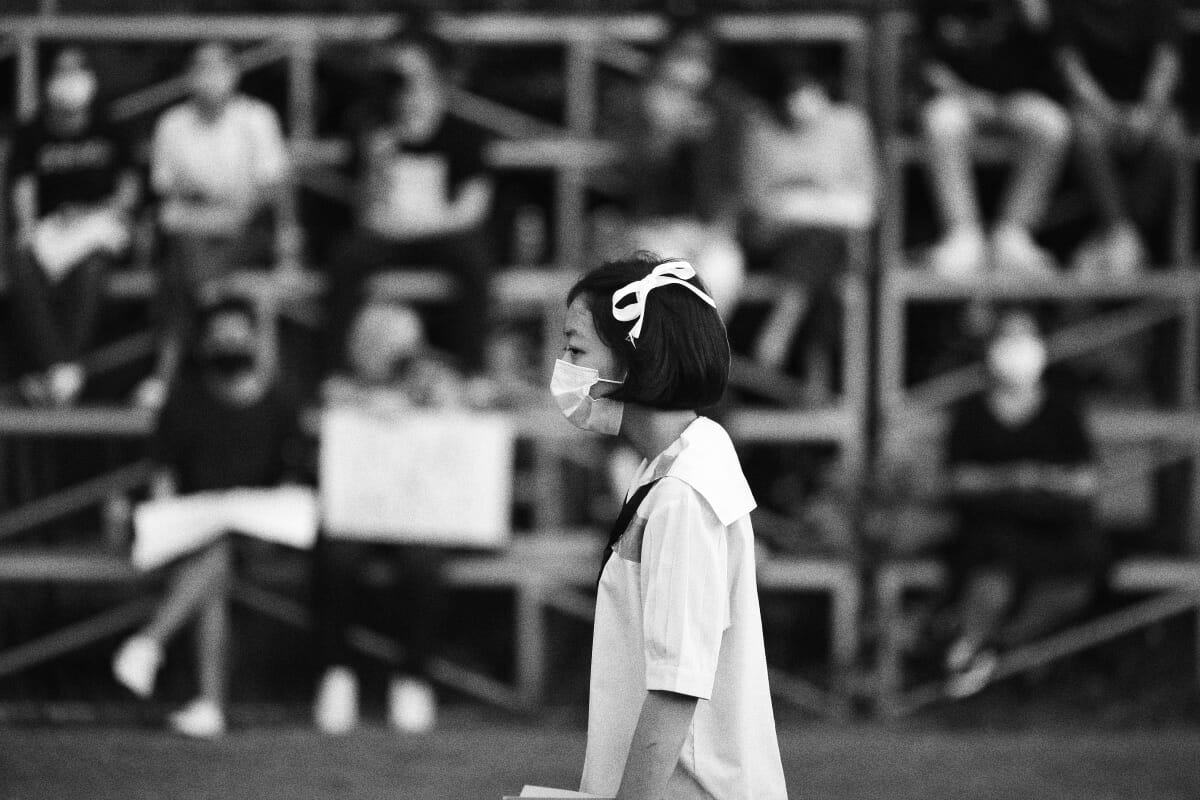

But even with the tough stance of the West and various international organisations, problems with Article 112 remain. In fact, since the nationwide protests in Thailand that broke out in mid-2020, the multiplying lèse-majesté cases have gravely impacted the Thai image, particularly regarding the appalling human rights situation in the country.

Many Thais have been arrested and thousands of websites deemed insulting to the monarchy closed down (including the Royalist Marketplace group page with more than a million members). Today, Thailand has the harshest punishment for lèse-majesté violations in the world. Ironically, this is a country where most Thais are said to possess an immense respect for their kings for their benevolence, compassion and forgiveness.

Special Report: Roundup of 2024

Trends, Challenges, and the Call for Reform

Despite the transition to civilian governance, the enforcement of Article 112 in 2024 has continued to have profound implications, demonstrating its entrenched role in shaping Thailand’s sociopolitical landscape. This report, written in December 2024, critically examines the application of Article 112 throughout the year, with a focus on prosecution trends, systemic judicial challenges, the exclusion of Article 112 cases from amnesty frameworks, and the broader implications for society and human rights.

Special Report: June 2024

Justice Denied

112WATCH publishes its special report of June 2024 titled, "Justice Denied: The Impact of Article 112 on Thailand's Political Freedom and Human Rights." One of the main focuses is on the recent death of a Thai activist, Netiporn 'Bung' Sanesangkhom., who went on a hunger strike to protest against her imprisonment. She was charged with lèse-majesté charges. Her death may or may not change the lèse-majesté situation.But it has already cuased a huge impact on the overall state of human rights in Thailand. This special report summarises the current lèse-majesté situation of Thailand.

Special Report: 2023/2024

Special Report: 2022-2023

2022 Summary of 112 Cases

Throughout 2022, political prosecution continued with cases from protests during the APEC2022 Summit involving arrest of civilians and summon warrants issued to activists. New arrests on the basis Section 112 (Lèse-majesté) continued to be reported periodically while many of those prosecuted for violation of the Emergency Decree continued with their defense with most cases concluding with acquittals.

According to statistics from TLHR (Thai Lawyers for Human Rights), at least 1,886 people in 1,159 cases were prosecuted due to political participation and expression since the beginning of the “Free Youth Movement” protest from 18 July 2020 to 30 November 2022. Among this number are 283 minors under 18 years old in 210 cases. Compared to the end of October 2022, 22 people in 14 cases were added to the statistics (counting only those who have never been charged before). If individuals prosecuted in many cases are counted, the number would be as high as 3,710 prosecuted individuals.

The prosecutions can be categorised according to key charges including the “royal defamation or lèse-majesté” charge, the “sedition” charge under Section 116 of the Criminal Code, Charges of violation of the Emergency Decree, Charges under the Public Assembly Act, Charges under the Computer Crime Act, and Contempt of court charge. But the highlight here is on the “royal defamation or lèse-majesté” charge under Section 112 of the Criminal Code which incurred at least 221 individuals in 239 cases.

An addition of 4 individuals in 3 cases were prosecuted under Section 112 (Lèse-majesté) of Thailand Criminal Code while 8 cases were concluded in November.

Four new individuals in 3 cases prosecuted under Section 112 (Lèse-majesté) were added to the statistic with at least one defendant, Sombat Thongyoi, remain detained for over 7 months while waiting for appeal.

The 4 individuals prosecuted in 3 cases included Warinthip Watcharawongthawee or “Xiao Pao” Faiyen, a citizen who once release to the press regarding the preparation to found a political party ‘Faiyen’. Xiao Pao was arrested and charged at Prachachuen Police Station following the accusation made by Anon Klinkaew, the leader of the People’s Centre for the Protection of the Institutions (CCP), for singing ‘. . . Lucky to have the Thai people’ by Faiyen in front of Bangkok Special Prison during September 2022.

Meanwhile, Jitrin Plakantong or “Karim Thalufah” surrendered to the police after became aware of the arrest warrant issued since March 2022 from allegedly burning the portrait of the King at the front of Rachawinit School during the protest on 19 September 2021. Karim was the fourth to be prosecuted in this case after Sam, Max and Miggy Bang who were previously accused but was granted bail later in November.

The court also concluded a total of 8 cases charged under Lèse-majesté in November, one of which was Jarat‘s case charged for criticizing Sufficiency Economy Philosophy of Rama IX on Chanthaburi Page. The Nonthaburi Court of Appeal Region 2 reversed the Court of First Instance verdict stated that Section 112 of the penal code (Lèse-majesté) may be interpret to protect late king as any defamation, insult or threat to the late king could affect the current king.

Furthermore, the case of “Petch” Thanakorn, a 19 year-old youth who participate in public speech on the 6 December 2020 at Wongwian Yai, was concluded guilty at Central Juvenile and Family court. Despite not mentioning any name, the court ruled that Section 112 (Lèse-majesté) also cover the monarchy constitution. In December, Petch was sentenced to 18 months in prison (but sentence suspended).

To have such a board interpretation of Section 112, protecting late king and the monarchy constitution without any define scope will continue to allow obscure implementation of this criminal code affecting freedom of expression as opinion regarding the monarchy constitution and may lead to legal consequences.

The other 6 cases were concluded with the defendants pleaded guilty: 4 of which were at the criminal court. Among the cases, “Nacha” was sentenced to jail term with suspension while other 3 defendants, Suthitep, Pitakpong and Panitarn, were sentenced to 3-5 years jail term without suspension. As a result, the 3 later cases had filed for appeal.

At the same time, “Joe” case charged for sharing an online post from Free Youth Facebook Page concluded with 2 years of suspension from Lampang Provincial Court while Pithayut ’s case of allegedly burning the portrait Rama X at Udonthani received a verdict to wait for sentencing hearing.

These cases involved everyday citizens. Many defendants did not participate in political protests but only express their opinion or shared an online post. To receive jail term without suspension still reveals violence resulting from Section 112 (Lèse-majesté) punishment as well as the perception or ideology of those in the judicial system.

Note: This report is composed based on information provided by TLHR. See details here: https://tlhr2014.com/en/archives/51466

Ongoing Crisis

The number of individuals charged with lèse-majesté has reached 100, as confirmed by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (as of June 2021). The overwhelming majority of these cases stemmed from online political expression and the participation in peaceful pro-democracy demonstrations that took place between August 2020 and March 2021. According to information compiled by TLHR, between 24 November 2020 and 11 June 2021, 100 individuals have been charged under Article 112 of Thailand’s Criminal Code (lèse-majesté). Of these, eight are children (i.e. individuals under the age of 18). Article 112 imposes jail terms for those who defame, insult, or threaten the King, the Queen, the Heir to the throne, or the Regent. Persons found guilty of violating Article 112 face prison terms of three to 15 years for each count.

After a two-year pause, in late November 2020, prosecutions and arrests under Article 112 resumed in response to the nationwide pro-democracy protests that swept Thailand for most of 2020. During many of the pro-democracy demonstrations, protesters broke Thailand’s longstanding political taboo by directly criticizing the monarchy and calling for reforms of the institution. This second wave of lèse-majesté charges was anticipated by Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, who, on 19 November 2020, announced that the government would enforce “all laws and articles” against pro-democracy leaders and protesters. Following Prayuth’s announcement, authorities have actively prosecuted, arrested, and detained pro-democracy activists and peaceful protesters who made public criticism of, or comments on, the Thai monarchy during protests as well as on social media platforms. Prominent pro-democracy activists have been especially targeted. Some of them face numerous prosecutions under Article 112 in connection with multiple cases, which could result in very long prison terms.

Many lèse-majesté defendants have been subjected to a systematic denial of bail by the courts, both during investigation and pending trial. Since November 2020, authorities have detained at least 17 individuals for alleged violation of Article 112. Although, as of June 2021, all lèse-majesté defendants have been released on bail, many of them were freed under the conditions that they would not engage in activities that cause further damage to the monarchy and not participate in activities that can affect public order.

As the second wave of lèse-majesté prosecutions began, Thailand also recorded the longest prison sentence ever imposed under Article 112. On 19 January 2021, the Bangkok Criminal Court sentenced 65-year-old former civil servant Anchan Preelert to 87 years in prison on 29 counts of lèse-majesté over online posts. Her sentence was reduced to 43 years and six months, in consideration of her guilty plea.

The day before, the Bangkok Criminal Court convicted writer and poet Siraphop Kornaroot of lèse-majesté for his online articles and poems. Siraphop was sentenced to four years and six months in prison. However, he was immediately released upon the court’s decision, because he had already spent four years and 11 months in pretrial detention following his arrest on 1 June 2014. His detention was declared arbitrary by the United Nations (UN) Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) on 24 April 2019, before his release on bail on 11 June 2019.

Since November 2020, various UN human rights monitoring mechanisms have expressed concern over Thailand’s growing number of lèse-majesté prosecutions and increasingly severe application of Article 112. They have also repeatedly called for the amendment or repeal of Article 112.

112 Watch joins the FIDH and TLHR in reiterating our calls on the Thai government to refrain from carrying out arrests, prosecutions, and detentions of individuals for merely exercising their fundamental right to freedom of opinion and expression. FIDH and TLHR also urge the Thai government to amend Article 112 to bring it into line with Thailand’s human rights obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). For further detail see, https://www.fidh.org/en/region/asia/thailand/lese-majeste-epidemic-reaches-new-milestone.

The Protests of 2020

Article 112 of Thailand’s Criminal Code is fundamentally incompatible with the right to freedom of expression. The Thai government must immediately end all criminal proceedings under Article 112 and repeal the provision in its entirety. In 2020, youth-led, pro-democracy protests swept across Thailand, with protesters calling for a new government, a new constitution, and the end to the harassment of activists and government critics (many anti-monarchist refugees were killed or forcibly disappeared while hiding in Thailand’s neighbours.) As the movement gained momentum, protesters began to openly question the monarchy, a development without precedent in modern Thai history. Activists called for curbs on the power of the monarchy, Thai social media users posted about the long periods of time the king spent outside the country, and protesters donned costumes poking fun at the king’s fashion choices. When the monarchy is under threat, Article 112 becomes a weapon.

Authorities at first tried to stymie the protest movement and suppress discussion of the monarchy by applying other laws and using force to disperse protesters. However, as these efforts failed, the government resorted to the renewed application of Article 112. In November 2020, Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha announced that the government would consider bringing lèse-majesté charges against protesters, ending a three-year de facto moratorium on the use of Article 112 (The use of Article 112 coming to a halt in late 2017 at the wish of King Vajiralongkorn as part of him trying to preserve a good image of the monarchy). According to Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, Thai police have opened investigations into at least 59 individuals under Article 112 since 24 November 2020. Most were prominent activists associated with the protest movement. Several face investigations in multiple cases and could spend decades behind bars if prosecuted and convicted.

Pimsiri Petchnamrob has become the subject of an ongoing lèse-majesté investigation relating to her participation in a peaceful protest. A summon issued by the police indicates that her investigation stems from her citation of a UN expert during a speech at the protest. In the speech, she quoted a statement by former UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression David Kaye that Article 112 is incompatible with international human rights law.

In January, courts convicted two individuals on lèse-majesté charges in relation to alleged insults to the monarchy made years earlier. In one case, a Bangkok court sentenced a civil servant to 43 years’ imprisonment under Section 112 for reposting videos on Facebook and YouTube. Most of the lèse-majesté cases initiated since November 2020 are in the investigatory stage and those accused remain at liberty. However, on 8 February 2021, the Attorney General formally charged four prominent activists under both Article 112 and Article 116, which punishes the crime of sedition. The Bangkok Criminal Court at first denied their request for bail, but later set them free under conditions. Article 112 does not comply with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which protects the right to freedom of expression. While the right to freedom of expression can be limited to protect the reputation of others, criminal penalties are never a proportionate penalty for reputational damage. Moreover, laws offering special protection to heads of state and high-ranking public officials invert the fundamental democratic principle that the government is subject to public scrutiny. Human rights experts and bodies have repeatedly warned against lèse-majesté laws and called on Thailand to repeal it. But their warning has been inconsistent at times.

Volunteers Needed for 112WATCH Project to help 112Watch and its partners accomplish critical research and advocacy. Find out more here.