What is Article 112?

Lèse-majesté, or the crime of injury to royalty, is defined by Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code, which states that defamatory, insulting or threatening comments about the king, queen and regent are punishable by three to 15 years in prison. In the past decades however, Article 112 has been dangerously politicised. It has been used as a political weapon, at first to undermine political opponents and later to attack anyone with different political ideologies. It also points to the injustice caused by the Thai government in defending the use of Article 112.

Awareness Raising

112's Problems

Problems from the Legal Provision

The penalty rate of three to fifteen year imprisonment is too high and comparable to an offence of preparation to commit insurrection, manslaughter, or kidnapping of a minor younger than fifteen years. The minimum penalty rate of three years is also too high. Even though the case could be trivial, the Court is left with no discretion but to impose at least this penalty rate.

There is a vague element of crime, particularly regarding the term “insult” which has been interpreted so widely covering a variety of acts or expressions.

Article 112 protects persons holding different positions including the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent, or the Regent, equally and indiscriminately, even though the damage done to the King should be more severe than the damage done to other personalities.

Article 112 is included in the “Title I” on “Offences relating to the Security of the Kingdom.” Therefore, its interpretation and enforcement can be cited for the sake of maintaining national security and that would do a disservice to the defendants.

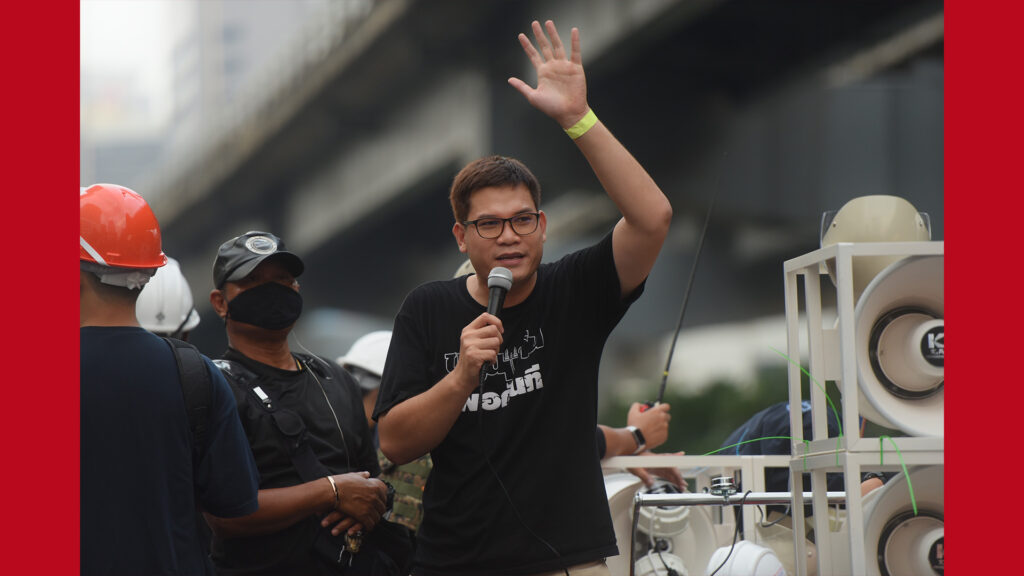

Problems from 112's Enforcement

Article 112 has been subjected to extensive interpretation and use in order to criminalise a variety of actions without clear boundaries. It impossible for ordinary persons to understand which kind of act constitutes the offence.

Any ordinary person can bring charges against another person invoking Article 112. It does not oblige the injured party to make the complaint. As a result, Article 112 has been used to accuse many individuals, sometimes frivolously.

Law enforcement officials involved with the prosecution per Article 112 have often found themselves subject pressure from society. Consequently, it is difficult for them to make any discretion in favour of the defendants, that is, by refusing to indict the case, or allowing the alleged offenders to have bail or dismissing the case.

112's Interpretation

Even though an offence against Article 112 must be confined among terms of defamation, insult and threatening of the persons protected by the legal provision including the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent, or the Regent, but in reality it can be interpreted in different ways to cover more acts.

In a verdict by the Supreme Court in the case against Nutchakit, the Court interpreted that the mention of King Rama IV was an offence, or in the case against Nopparit who was accused of forging documents claiming they belonged to Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn and Thanakon who was prosecuted on the charge simply for clicking ‘like’ and making a comment about a royal dog “Khun Thong Daeng.”

Prosecutions beyond what is provided for by the letter of law have made it difficult for most people to figure out the boundary of the law.

Examples of Cases

In most cases, the Court of Justice often imposes five years per count, for example, in the cases against Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, Daranee (Da Torpedo), and Ampon Tangnoppakun (Uncle SMS). Meanwhile, in several other cases, the Court opted to impose much harsher penalties including the case against Piya Julkittipan who was sentenced to nine years for his Facebook comments critical of the monarchy, Charnvit who was sentenced to six years for distributing lèse-majesté leaflets, and the case of bookseller who sold the Thai translation of “The Devil’s Discus: An Inquiry into the death of Ananda, King of Siam” who was sentenced to three years.

Under the rule of the military government, the Military Court often imposes 10 years of imprisonment per count, for example, the cases against Hassadin Uraipraiwan and 9 others who was accused of producing “Banpod”' audio clips criticising the royal family, Pongsak Sriboonpeng Thiansutham and Sutthijitseranee (critical comments toward the monarchy on Facebook), and Samak Pantay (damaging the portrait of the King and Queen). Meanwhile, the Court may impose harsher or lighter penalties such as the case of Sasivimon who was sentenced to eight years per count for her insulting comments about the monarchy, Nirand for five years per count (for publicising fame statement of the Bureau of the Royal Household), and Opas Chansuksai (writing graffiti insulting the monarchy) for three years per count.

What can be Said about the Monarchy?

From its legal provision, Article 112 simply protects those persons holding four positions only and does not cover the “monarchy.” Therefore, criticism about the monarchy as an institution should be doable without criticising the persons or making other criticisms about other personalities relating to the monarchy.

Other royal family members, the Privy Council, close aids, the Crown Property Bureau, and the Royal Project are not protected by the legal provision and any criticism about them should be doable without making a gesture to defame, insult or threaten them. But given the general climate in Thai society and politics, the over-interpretation and over-enforcement of the law, it has made the boundary of the possible expression very dubious and unclear.

Effects on Society

Article 112 has been regularly invoked to crack down on political opponents and used by all political factions. But the target is not only political factions. The massive number of people prosecuted by Article 112, the harsh penalty rate coupled with the trial procedure whereby most of the accused are denied bail with the Court ordering a secret trial, have engendered a burgeoning climate of fear.

Fear has engulfed the whole of society with the notion that the monarchy is untouchable and unspeakable and people need to practice self-censorship. Utmost caution is needed when discussing any issues about the monarchy both during personal and public communication. It has gravely compromised Thai people’s knowledge and understanding about the monarchy. In addition, given that Article 112 has been used for serious criminalisation, it has been abused for revenge even among people who are related to each other, for example, the case of an older brother who took his younger sibling to the Court on this charge by alleging that his brother was making a lèse-majesté remark, or the cases in which fake Facebook pages have been created to retaliate against others accusing them of committing lèse-majesté offences as a result of personal feuds such as the above-mentioned case of Sasivimon.

Affects on Monarchy

When news about how a number of people have been prosecuted using Article 112 and how they have been sentenced to harsh penalties is made public, it has drawn criticism that the law has been used to stifle freedom of expression and human rights. It sometimes has an indirect ramification on the image of the monarchy in Thailand, particularly when such news is sensationalised in the international media. It propagate negativity and distrust for the monarchy. In addition, since it is highly sensitive to discuss issues of monarchy in Thailand, it has distanced the institution from the perception of ordinary persons making it less accountable and more irrelevant in the modern world.

RECOMMENDATIONS

112Watch Advocates Changes

- To have Article 112 excluded from the “Title I” on “Offences relating to the Security of the Kingdom”.

- To add another Title on “Offences relating to the Reputation of the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent, or the Regent”,

- To segregate the protections between the King and other personalities including the Queen, the Heir-apparent, or the Regent

- To change the penalty rate by removing the minimum punishment and fixing the maximum punishment to three years and to separate between the ordinary defamation and the act on publication.

- To include as a defence if the criticism is made in good faith

- To include as a defence if it can be proven that the statement made is true and serves public interest and;

- To prohibit an ordinary person to bring such charges against another person and the legal standing should be confined to just the Bureau of the Royal Household.

The international community can play an important role in applying pressure on the Thai government to seriously consider the reform of the lèse-majesté law, for ultimately the protection of the basic human rights of the Thai people, as well as the responsibility of Thailand in supporting the global human rights agenda.

How Possible are the Proposed Amendments for Article 112?

After its latest revision by a Declaration of the Revolutionary Council in 1976, Article 112 has never been subjected to change ever again by any government. In May 2012, more than 10,000 people signed a petition proposing the Parliament to have Article 112 amended per the proposals of the Nitirat Group, but the then Speaker of the House of Representatives, Somsak Kiatsuranont, determined that the proposed amendments were about the amendment of the law concerning the monarchy, not the law about people’s rights and freedoms, and thus it was not constitutional right of the people to propose such amendments.

Note: 112Watch would like to thank iLaw for the information on this page.

Site artwork by PrachathipaType

Contact Us | Volunteer & Join Us | © 2022, 112Watch | Privacy Policy