Academic Freedom and Authoritarian Persistence: The Paul Chambers Case and Thailand’s Human Rights Crisis in 2025

A SPECIAL REPORT – compiled by Nana Tashiro, in collaboration with 112WATCH

June 1, 2025

1. Introduction

Thailand’s political landscape in 2025 reveals a troubling paradox. Despite a formal return to civilian rule following the 2023 general election, the entrenched influence of the military and monarchy continues to impede genuine democratic reform. The arrest of Dr. Paul Chambers—a respected American scholar—under Article 112 represents a serious threat to academic freedom. His prosecution illustrates the persistent use of Article 112 as a tool of state repression and underscores the structural barriers to democratisation under the current regime.

Using the Chambers case as a lens, this article examines Thailand’s political stagnation across three interrelated dimensions: the repressive deployment of Article 112, the fragile legitimacy of civilian governance, and Thailand’s shifting geopolitical posture amid intensifying U.S.–China rivalry.

2. The Chambers Case: Criminalising Scholarship

2.1 Legal Analysis

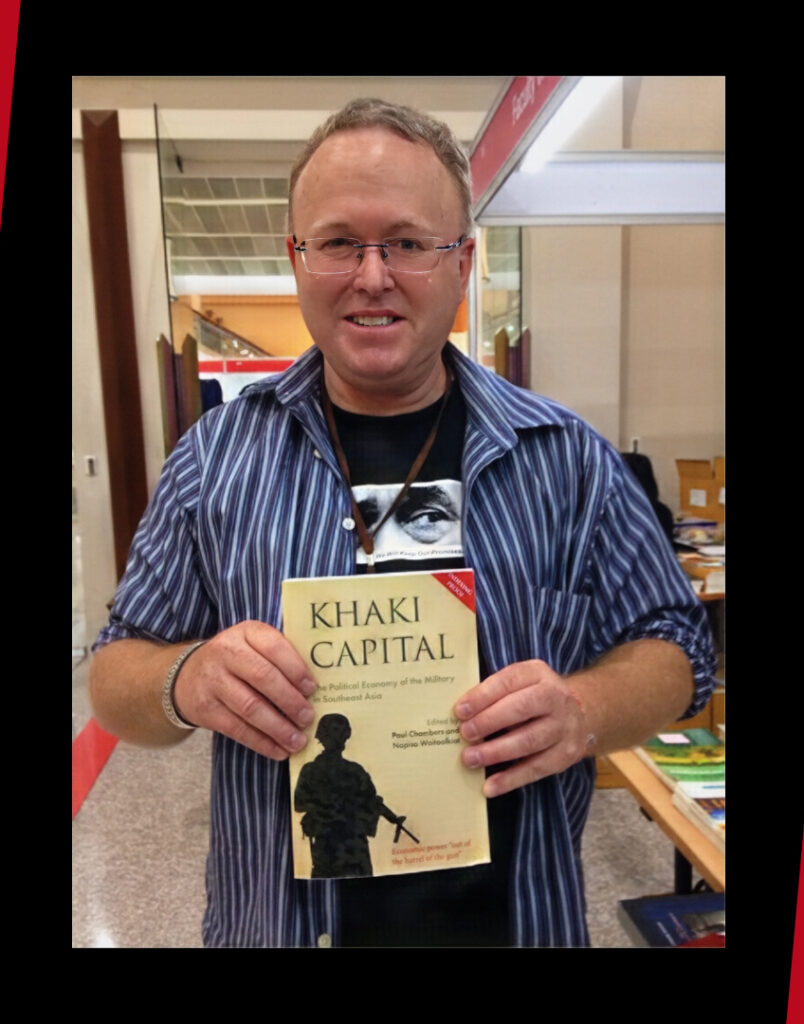

The arrest and judicial harassment of Dr. Paul Chambers on 8 April 2025 represents a pivotal episode in Thailand’s suppression of academic freedom. Chambers, a political scientist at Naresuan University known for his work on civil-military relations, was charged under Article 112 and the Computer Crimes Act (Section 114). The charges arose from a webinar invitation titled “Thailand’s 2024 Military and Police Reshuffles: What Do They Mean?”, hosted by Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. Chambers denies all allegations, stating he “neither wrote nor published the blurb on the website” (Ratcliffe, 2025).

According to Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (2025), the case raises several key concerns:

- The increasing use of vague, punitive legislation to suppress academic inquiry;

- The military’s direct involvement in filing complaints against scholars;

- Procedural irregularities, including arbitrary pretrial detention and retaliatory immigration measures.

Chambers’ visa was revoked under Section 12(8) of the Immigration Act (1979), citing a threat to public “good morals”—a move amounting to extrajudicial punishment (Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, 2025). These violated principles of due process and the presumption of innocence, particularly egregious given Chambers’ long-term residence and minimal flight risk (Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, 2025). The Phitsanulok Provincial Court’s denial of bail further undermined judicial impartiality and contravened both Thailand’s Constitution and international legal standards, notably Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966) and General Comment No. 35 (2014), which stress that pretrial detention must be exceptional.

This case demonstrates how Article 112 has transformed from a law intended to protect the monarchy into a tool of political repression. Its vague language allows authorities to reinterpret academic discourse as a threat to national security (112WATCH, 2024). In Chambers’ case, a scholarly analysis of bureaucratic reshuffles was distorted into an alleged act of sedition. Such elasticity in legal interpretation is a hallmark of authoritarian regimes.

Equally troubling is the pattern of legal exceptionalism in the Article 112 prosecutions. These cases often proceed with insufficient evidence, yet bail is frequently denied (Thai Lawyers of Human Rights, 2024), reinforcing the perception that the judiciary serves military and royalist interests. Rather than protecting justice, the legal system appears complicit in silencing dissent through selective enforcement.

2.2 Procedural Irregularities

The legal and administrative handling of Chambers’ case reveals procedural abuses aimed at deterring dissent and punishing critical scholarship.

- Visa Revocation: Prior to any trial or conviction, Chambers’ visa was cancelled under a vaguely defined morality clause in the Immigration Act. Invoking Section 12(8) under Section 36, authorities used immigration law to criminalise his academic presence without judicial oversight (Thai Lawyers for Human Rights, 2025).

- Denial of Bail: Despite Chambers’ established ties to Thailand and his professional status, the court denied bail—an increasingly common practice in lèse-majesté cases. This contradicts international legal standards, such as Article 9 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), which guarantees protection against

- Military Interference: The initiation of legal proceedings by military actors further blurs the line between civil and military spheres. It raises serious concerns about the impartiality of the judiciary and the broader coercive intent behind such prosecutions.

These irregularities reveal how legal and administrative instruments in Thailand are weaponised to enforce ideological conformity, eroding the rule of law and public trust in legal institutions.

3. Democratic Façade, Authoritarian Core

Thailand’s 2023 general election initially appeared to signal a shift toward democratic renewal. The Move Forward Party, which campaigned on a progressive platform including the reform of Article 112, won the largest share of seats in the House of Representatives (Curtis, 2024). However, the military-appointed Senate blocked party leader Pita Limjaroenrat from assuming the premiership (Curtis, 2024), undermining the democratic mandate. Ultimately, the Pheu Thai Party, once a populist challenger to military dominance, formed a coalition with conservative and military-aligned factions, securing Srettha Thavisin’s appointment as prime minister and marking a retreat from democratic reform (Ewe, 2023).

By 2024, Pheu Thai leadership transitioned to Paetongtarn Shinawatra, daughter of exiled former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who returned to Thailand under suspiciously lenient judicial circumstances in 2023 (Head et al., 2024). This dynastic shift demonstrates the political elite’s willingness to preserve power structures through compromise with the military-monarchy alliance, rather than confronting entrenched authoritarianism. Despite electoral legitimacy, Paetongtarn’s government has preserved—and in some cases expanded—repressive mechanisms inherited from the military junta.

In this context, the Chambers case is not an anomaly but a product of systemic continuity. It illustrates how authoritarian legal instruments are now wielded not by a military junta but by an elected civilian regime. This further complicates international responses and blurs the line between democratic form and authoritarian substances. The enduring use of these laws by civilian leaders indicates not just inertia but strategic complicity—where electoral legitimacy is used to entrench, rather than dismantle, mechanisms of repression

4. Authoritarian Persistence, Academic Repression, and Shifting Geopolitics

The arrest of Dr. Paul Chambers in April 2025 marked a significant escalation in Thailand’s authoritarian governance, particularly in state responses to dissent and academic criticism. His case represented an unprecedented extraterritorial application of Article 112, raising critical concerns regarding academic freedom and the suppression of open discourse.

Chambers’ prosecution did not occur in isolation. Two months prior, Thai authorities forcibly deported 40 Uyghur refugees to China, violating international law and the principle of non-refoulement (Human Rights Watch, 2025). This act drew immediate condemnation from the United Nations, international human rights organisations, and Western governments (Human Rights Watch, 2025), prompting the United States to impose targeted visa sanctions on senior Thai officials (Strangio, 2025). The deportation was widely interpreted as a strategic concession to Beijing, underscoring Thailand’s prioritisation of geopolitical interests over human rights obligations.

Whereas the Uyghur case was framed in terms of realpolitik, Chambers’ arrest revealed a broader authoritarian shift. Unlike the deportations, which aligned with Chinese demands, the prosecution of a U.S. academic provoked sharp rebukes from Western democracies and rights organisations. The case demonstrated the Thai state’s increasing willingness to criminalise academic analysis—even when conducted abroad—and its expanding use of legal mechanisms, particularly Article 112, to suppress not only domestic dissent but also international scholarly engagement.

Taken together, these incidents illustrate a concerning pattern: Thailand’s growing intolerance of criticism coincides with its deepening alignment with authoritarian powers. This trend has profound implications for academic freedom and the country’s international standing. Scholars and civil society actors increasingly perceive Thailand as an unsafe environment for critical inquiry. Local researchers face heightened risks, while foreign academics are deterred from engaging with Thai political issues. The long-term consequences include intellectual isolation and diminished participation in global research networks.

Thailand’s foreign policy has undergone a parallel transformation. While Bangkok historically maintained a balanced posture between the U.S. and China in the post-Cold War era, recent developments indicate a decisive tilt toward Beijing (Chivvis et al., 2023). This realignment extends beyond diplomatic and economic cooperation to the adoption of China-style governance tools, including digital surveillance, information control, and civil liberties suppression (Feldstein, 2021). As strategic ties with China deepen, Thailand’s adherence to international human rights norms appears increasingly tenuous. Therefore, the Chambers case epitomises this geopolitical shift. The current regime has grown more assertive in confronting democratic partners, buoyed by political insulation from Beijing. This alignment reduces external pressure for reform and emboldens repressive domestic practices.

However, this strategy entails significant risks. Thailand’s retreat from rights-based diplomacy and its deteriorating democratic reputation threaten to alienate traditional allies (Chivvis et al., 2023). The erosion of academic freedom undermines the country’s soft power, credibility in multilateral forums, and ability to attract scholars, NGOs, and development partners. Once regarded as a potential democratic leader in Southeast Asia, Thailand is now increasingly perceived as a case of democratic backsliding.

In this context, laws such as Article 112 serve not only as instruments of domestic control but also as indicators of geopolitical orientation. Their persistent application reflects a strategic calculus: that domestic repression can coexist with alignment alongside authoritarian powers abroad. Yet, as the Chambers and Uyghur cases demonstrate, this approach may exact substantial costs in terms of international legitimacy, diplomatic influence, and long-term national interests.

5. Update

On 30 May 2025, Chambers has been cleared of lèse-majesté charges by the Office of the Attorney General due to insufficient evidence. The Thai Lawyers for Human Rights confirmed the case was dropped, as no direct link could be established between Chambers and the contentious material. Now free and back in possession of his passport, Chambers has left Thailand, closing a tumultuous chapter that underscores the precarious space between academic freedom and Thailand’s strict royal defamation laws.

6. Conclusion: A Call to Defend Academic Freedom and Dismantle Legal Repression

The arrest of Dr. Paul Chambers in April 2025 is far more than a legal anomaly—it is a warning bell. It marks a dangerous escalation in the Thai state's use of Article 112 and related laws to silence intellectual dissent, erode civil liberties, and sustain authoritarian rule. The case starkly reveals how entrenched political forces—both civilian and military—continue to manipulate the law to suppress critical thought and resist democratic reform.

This incident must galvanise urgent action from human rights advocates, academic institutions, and international actors. Defending academic freedom is not merely about protecting scholars; it is about safeguarding the public space for truth, accountability, and democratic dialogue. When a state criminalises peaceful, evidence-based analysis, it endangers not only individuals but the integrity of knowledge itself.

The persistence of Article 112 in its current form represents a structural threat to Thai democracy. Its vague language, broad interpretation, and harsh penalties provide a legal veneer for repression. Repealing or radically reforming Article 112 must be a central demand for all those committed to restoring democratic governance and human rights in Thailand.

Importantly, Dr. Chambers’ case is not an isolated incident. It must be understood alongside the prosecution of prominent Thai human rights lawyer Anon Nampa, who was sentenced to multiple years in prison for calling for monarchy reform in a peaceful speech (Front Line Defenders, 2025), and the tragic death of Bung Netiporn, a young activist who died in custody while on a hunger strike demanding the abolition of pretrial detention for political prisoners (Drury, 2024). These cases demonstrate the devastating and ongoing consequences of Article 112 for individuals, communities, and the democratic fabric of Thai society.

As an organisation committed to defending civil liberties, 112WATCH urges the international community to recognise that the Chambers case is emblematic of a broader authoritarian trend that requires a coordinated and immediate response. Sanctions, academic solidarity, and diplomatic pressure must be brought to bear.

This moment demands clarity and courage. The choice is between a society where truth is punished and fear prevails, or one where knowledge, debate, and human dignity are protected. The arrest of Paul Chambers, the sentencing of Anon Nampa, and the death of Bung Netiporn are not just individual tragedies—they are tests for all who believe in the right to think, speak, and dissent freely. We must meet this challenge without delay.

Report compiled by Nana Tashiro, in collaboration with 112WATCH.

References

Chivvis, C, S., Marciel, S., & Geaghan-Breiner, B. (2023). Thailand in the Emerging World Order. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/10/thailand-in-the-emerging-world-order?lang=en

Curtis, J. (2024). Thailand: Political developments 2023-24 and the banning of the Move Forward Party. House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10141/

Drury, F. (2024, May 15). Jailed Thai activist, 28, dies after hunger strike. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0v005j1j91o

Ewe, K. (2023, August 23). Thailand’s Populist Pheu Thai Party Finally Won the Prime Minister Vote—But at What Cost? Time. https://time.com/6307115/thailand-prime-minister-srettha-thavisin-pheu-thai/

Feldstein, S. (2021). Thailand’s Strategy of Control. In Steven, F (Eds.), The Rise of Digital Repression: How Technology is Reshaping Power, Politics, and Resistance (pp. 66 -133). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190057497.003.0004

Front Line Defenders. (2025). Repeated Criminalisation of Thai Human Rights Lawyer Arnon Nampa. https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/en/case/repeated-criminalisation-thai-human-rights-lawyer-arnon-nampa

General comment No. 35 on Article 9, Liberty and security of person, CCPR, CCPR/C/GC/35 (31 October 2014).

Head, J., Doksone, T., & Ng, K. (2024). Ex-PM's daughter picked as youngest ever Thai leader. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cd6yj26vz8yo

Human Rights Watch. (2025). Thailand: 40 Uyghurs Forcibly Sent to China. https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/02/27/thailand-40-uyghurs-forcibly-sent-china

Ratcliffe, R. (2025, April 8). American academic Paul Chambers charged with insulting monarchy in Thailand. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/apr/08/american-academic-paul-chambers-thailand-charged-insulting-monarchy

Res 2200A, UNSC, UN Doc S/2200A/XXI (16 December 1966).

Strangio, S. (2025, March 17). US Imposes Visa Restrictions on Thai Officials Over Uyghur Deportation. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2025/03/us-imposes-visa-restrictions-on-thai-officials-over-uyghur-deportation/

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights. (2024). ประมวลสถานการณ์ยื่นประกันตัวผู้ต้องขังทางการเมืองครึ่งปี 2567 (ม.ค. – ก.ค.) พบคำร้องขอประกันสูง 109 ฉบับ มีเพียงผู้ต้องขัง 6 ราย ได้ประกัน [Summary of the political detainee bail situation for the first half of 2024 (January – July): A total of 109 bail requests were submitted, but only 6 detainees were granted bail.] https://tlhr2014.com/archives/68919

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights. (2025). Statement: Calling on Thailand to Guarantee Basic Rights in the Criminal Justice System in Section 112 Case Regarding the Arrest of Dr. Paul Chambers. https://tlhr2014.com/en/archives/74771