How Lèse-Majesté Laws Create a Constitutional Blind Spot

Thailand's lèse-majesté legislation presents an extraordinary democratic contradiction: the most consequential laws remain beyond scholarly examination. This intellectual prohibition creates a system where legal provisions capable of destroying lives exist in a zone of academic silence—rendering Thailand's entire legal education system complicit in maintaining a constitutional governance impossibility.

April 22 2025

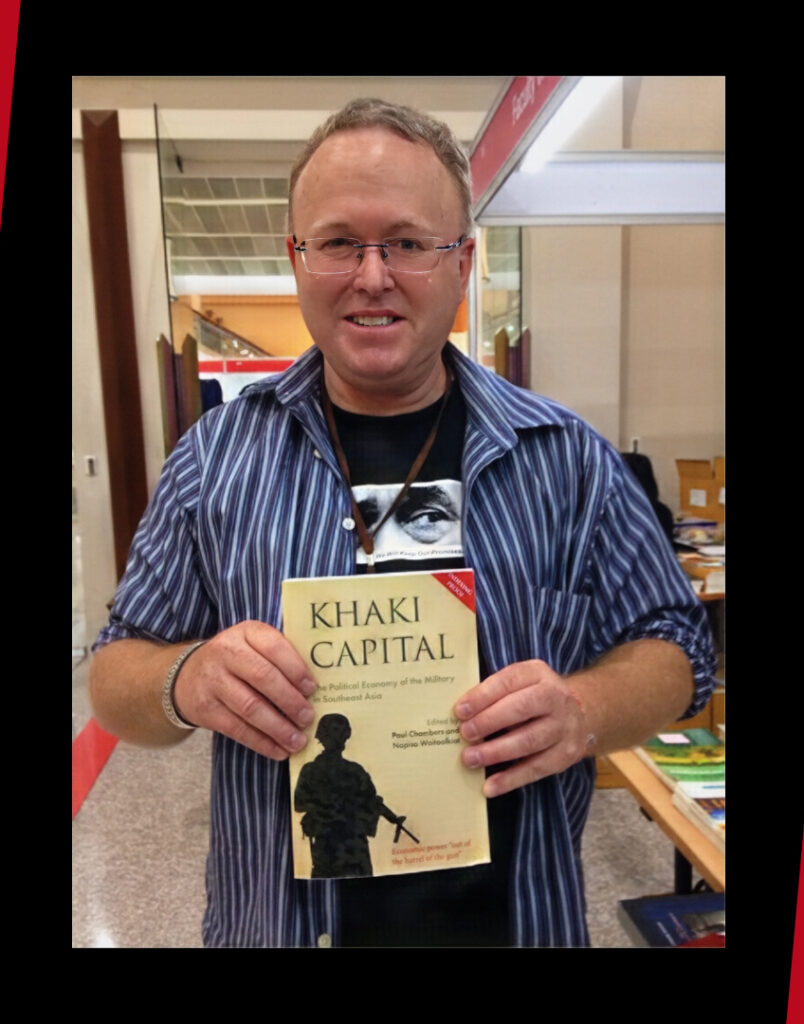

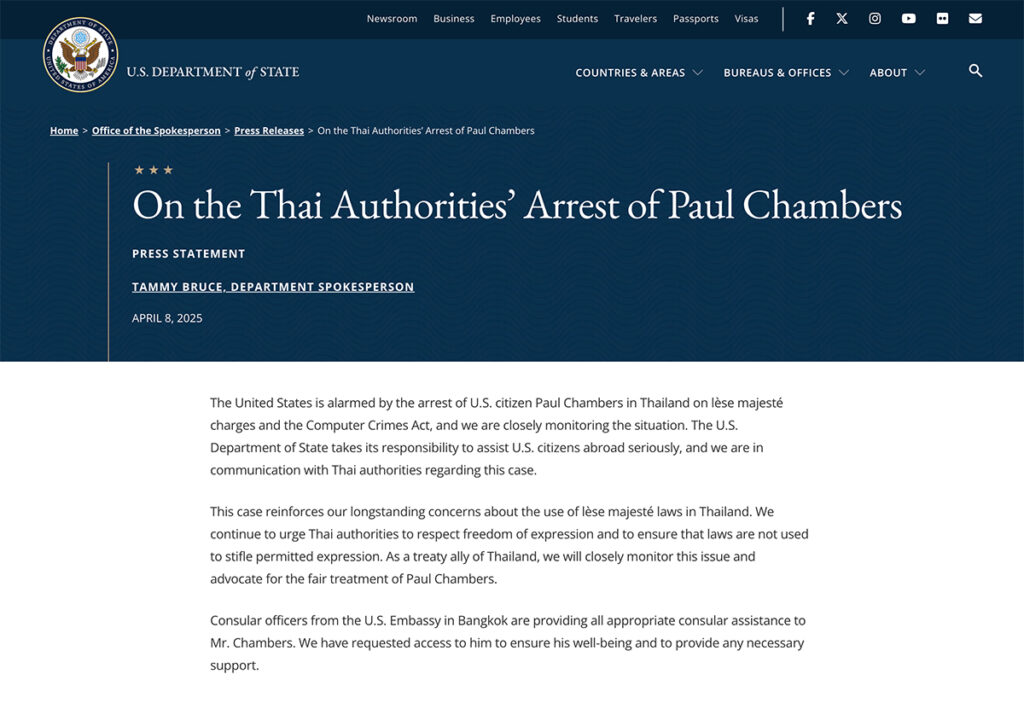

The recent arrest of American academic Paul Chambers exemplifies the aggressive enforcement patterns of Thailand's Section 112. Chambers, a 58-year-old lecturer with extensive teaching experience in Thailand, faced detention in Phitsanulok province after Thailand's military filed a complaint regarding content published on the website of Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies—a short blurb about Southeast Asian politics. Chambers denied writing the blurb. While released on 300,000 baht bail, he faces potential imprisonment of up to 15 years.

What's particularly alarming is that military officials who initiated Chambers' prosecution may themselves misunderstand the law they're weaponizing. This dangerous dynamic—where authorities with limited legal training can deploy Section 112 against scholarly discourse—creates tremendous vulnerability for academics. The military's involvement represents a dangerous game played against intellectual inquiry, targeting scholars whose work threatens entrenched power structures rather than genuinely protecting royal dignity.

Thailand's Exceptionalism

Thailand's approach stands in stark contrast to other monarchies with similar provisions. Saudi Arabia's anti-royal criticism laws have resulted in severe consequences, including links to journalist Jamal Khashoggi's killing. Yet even Saudi universities permit theoretical discussion of these laws in academic settings—something systematically avoided in Thai institutions.

Morocco's Article 179 criminalizes "undermining" the monarchy with penalties up to five years imprisonment, yet Moroccan law schools routinely analyze its jurisprudential basis and constitutional implications. Even Jordan, with strict provisions protecting King Abdullah II, allows academic examination within controlled educational environments.

Spain's experience offers particular insight—after the European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2018 that Spain violated free speech principles by imprisoning Catalans who burned royal photographs, Spanish legal academia engaged in robust debate that prompted reform. This evolutionary process remains entirely absent from Thailand's approach.

The Educational Void: Legal Complicity

The consequences of Thailand's educational omission transcend academic interest. When law students become lawyers, judges, and legislators without critically examining Section 112, they perpetuate a system where this provision exists beyond normal legal discourse. The statute transforms from merely a law into something resembling a sacred text—protected from analytical scrutiny routinely applied to other legal provisions.

This educational gap has created a generation of legal professionals incapable of addressing one of their nation's most controversial statutes. The paradox deepens when considering that carrying or referencing Thailand's Criminal Code (which contains Section 112) potentially becomes problematic itself. This Kafkaesque situation fundamentally undermines legal education and practice.

Thai Academics: Chilling Effect

For Thai professors, the situation creates intolerable professional anxiety. Several Thai academics report being under constant surveillance, living with the knowledge they may face prosecution at any moment. This monitoring creates a perpetual state of professional and personal uncertainty—scholars cannot predict which comment, lecture, or publication might trigger enforcement action.

This chilling effect extends far beyond those directly charged, fostering self-censorship that penetrates institutions supposedly dedicated to critical inquiry. Thai professors find themselves unable to discuss constitutional fundamentals with students, creating graduates incapable of addressing core questions about the relationship between monarchy and democracy.

Disproportionate Enforcement

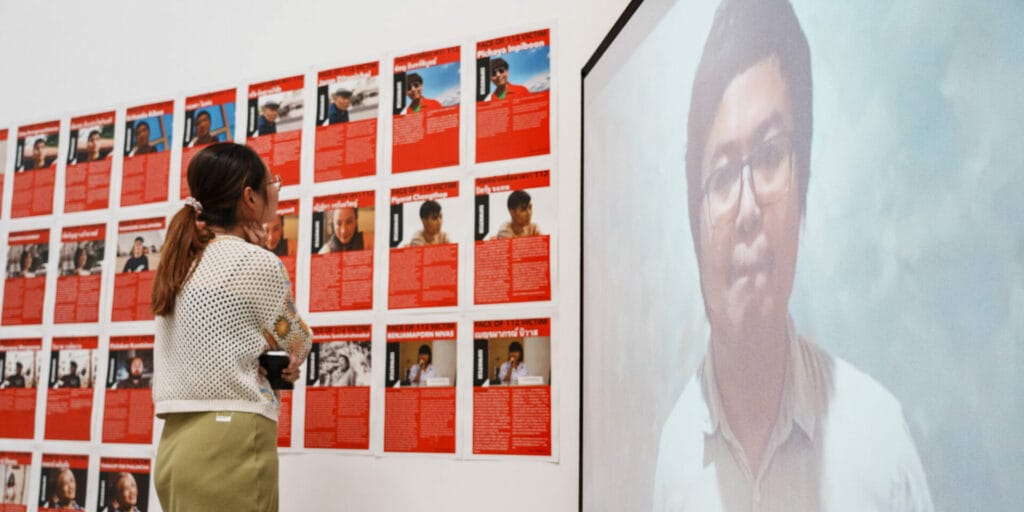

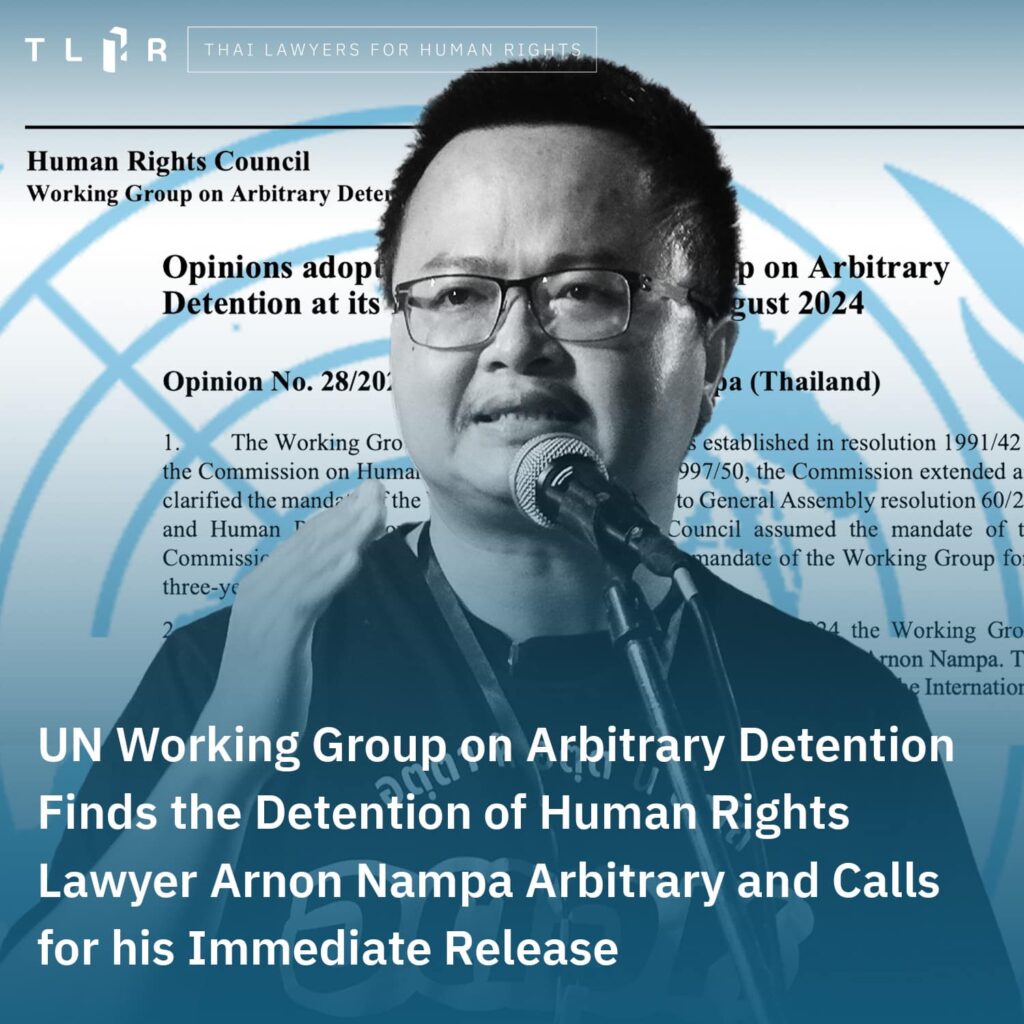

International organizations have repeatedly expressed concern about Thailand's application of these laws. The disproportionate sentences highlight Section 112's extraordinary nature—a man in northern Thailand received at least 50 years imprisonment, while a woman was sentenced to 43 years in 2021. Perhaps most emblematic was the two-year sentence given to a man for selling satirical calendars featuring rubber ducks that a court determined defamed the king.

Following Chambers' arrest, the United States State Department expressed alarm, noting longstanding concerns about Thailand's use of lèse-majesté laws. They urged Thai authorities to respect freedom of expression and ensure laws aren't weaponized against permitted expression. However, international pressure has produced limited reform results. Indeed, when reform efforts have emerged within Thailand, courts have ruled such moves violate the nation's constitution—effectively placing Section 112 beyond democratic reform processes.

Strategic Intimidation Through Selective Enforcement

Chanatip Tatiyakaroonwong, an Amnesty International researcher campaigning for political prisoners' release, identified the strategic intimidation behind actions like visa revocations: "The visa revocation is meant to send a message to foreign journalists and academics working in Thailand, that speaking about the monarchy could lead to consequences." This message extends not just to foreigners but to Thai citizens as well, particularly those in academic positions who might facilitate critical discussions about the monarchy's role.

The enforcement pattern reveals Section 112 functions beyond merely protecting the monarchy's dignity. It operates as a mechanism for controlling political discourse more broadly, establishing boundaries around acceptable political debate. This control extends beyond explicit royal criticism to encompass discussions about power structures, constitutional arrangements, and democratic reforms.

The Impossibility of Constitutionality

Without academic freedom to discuss, analyze, and critique Section 112, constitutional development in Thailand faces a fundamental impasse. False prosecutions will continue as the legal system lacks the intellectual foundation to distinguish between legitimate academic inquiry and genuine violations. The absence of legal scholarship surrounding lèse-majesté creates an environment where misinterpretations and overreach become inevitable rather than exceptional.

Unlike constitutional monarchies such as the United Kingdom, Netherlands, or Sweden, where academic discourse freely engages with royal power limitations, Thailand's approach creates a scholarly understanding gap that undermines constitutional jurisprudence development. Even Japan, which maintains respect for its emperor through social custom rather than criminal sanction, allows robust academic discussion of the imperial institution's constitutional position—something unimaginable in Thai universities.

Academic Courage is a MUST!

For Thailand's democracy to mature, its legal education system must evolve to include critical examination of all laws, including those protecting the monarchy. A law that cannot withstand academic scrutiny raises fundamental questions about its compatibility with democratic governance. The absence of Section 112 from legal curricula creates not just a knowledge gap but an ethical one—producing generations of legal professionals unequipped to engage with one of their nation's most controversial laws.

The Chambers case reminds us that Thailand's lèse-majesté laws remain actively enforced tools for controlling speech. While foreigners rarely face charges, their occasional prosecution serves as a powerful reminder that no one is entirely immune. For Thai academics and students, the message is clearer still—certain knowledge remains forbidden, certain questions unaskable, certain analyses unpublishable.

Until Thailand's educational institutions find the courage to incorporate critical examination of Section 112 into their curricula, the country will continue producing legal professionals unprepared to address one of their nation's most powerful and problematic laws. The silence surrounding Section 112 in Thailand's classrooms speaks volumes about the challenges facing the nation's democratic development and academic freedom.

The fundamental question remains unanswered and perhaps unanswerable within Thailand itself: How can a democratic society properly function when its legal professionals are systematically prevented from analyzing, critiquing, and potentially reforming laws with such profound impacts on freedom of expression? Thailand's democratic experiment cannot succeed while maintaining zones of intellectual prohibition incompatible with constitutional governance principles.

Prem Singh Gill

Prem Singh Gill is a Visiting Scholar at the Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia and a Visiting Scholar in Thai Public Universities.